Methodology

The DPI Map collects data based on a framework explained below. This framework provides a comprehensive view of the technical and governance characteristics of DPI, studying DPI through a set of attributes and indicators. Given its desk-based data collection methods, the DPI Map gathers data on a limited number of these indicators.

Based on a minimal set of benchmarks that are regarded as characteristics of DPI, we arrived at a “count” for DPI-like systems.

For digital ID systems, we counted if the country claimed to have a digital ID, whether it was active, enabled digital authentication, and was used by 2 more sectors.

For digital payment systems, we counted if the country had a payment system that was active and enabled real-time transactions, and was operated by the central bank wholly or partially.

For data exchange systems, we counted countries with active systems that were designed to exchange data across sectors.

DPI-likeness refers to systems most closely associated with being DPI.

DPI Conceptualisation and Measurement Framework

As governments, multilateral actors, and technology implementers collaborate towards making DPI a reality across the globe, the DPI Map asks: how prevalent is DPI across the planet?

To answer this, we had to wrestle with some fundamental issues. How does one define DPI as a concept? How do you translate any definition into foundational qualities that can be objectively measured across different national contexts around the world? This piece seeks to explain our approach in addressing these questions, to enable researchers, technical advisors, policymakers and advocates to understand the context of this data set and its limits, so they can effectively use it in their work.

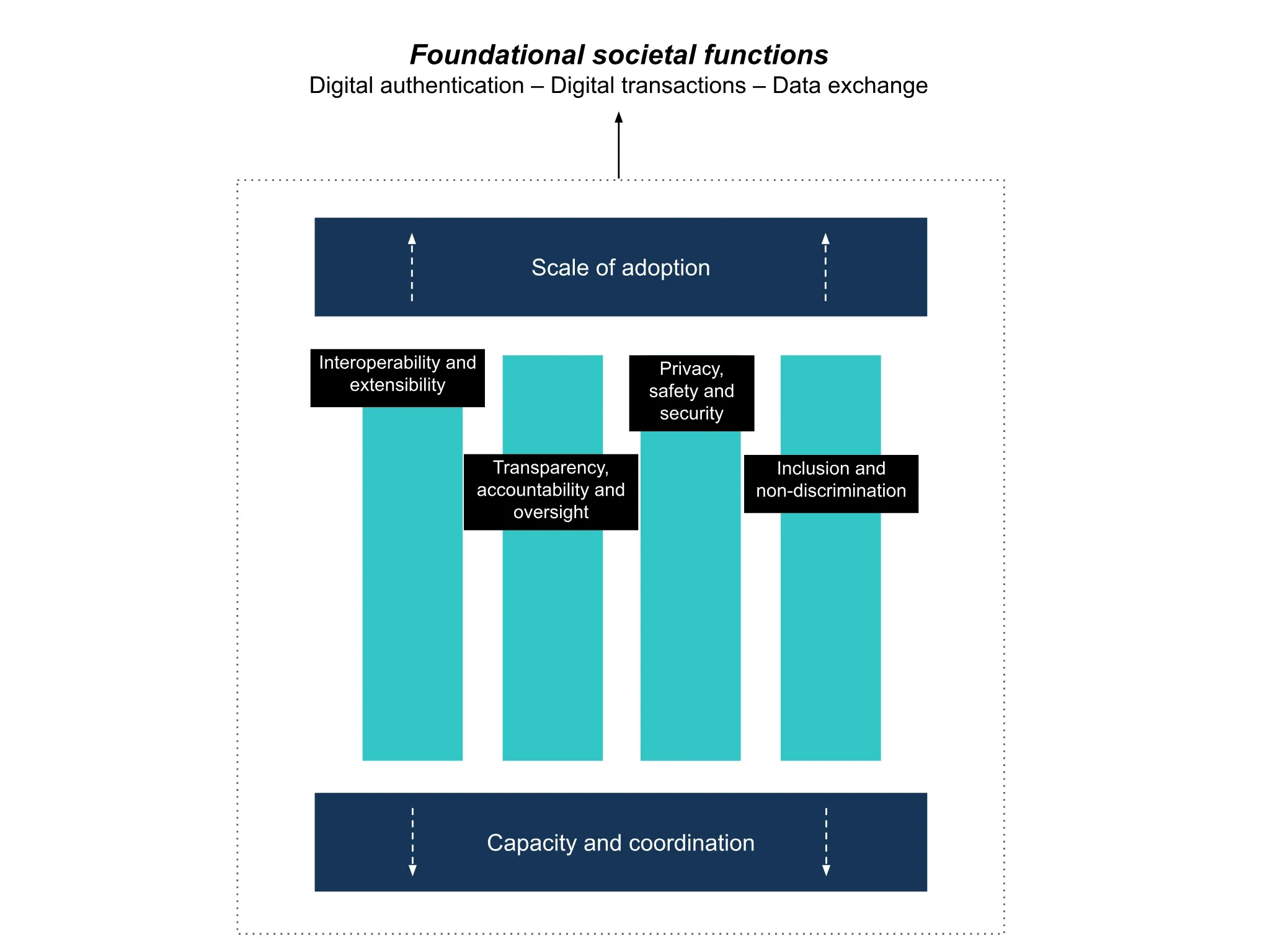

The resulting ‘Measuring DPI Framework’, offers a first take on translating the normative concept of DPI into a measurable framework to evaluate real-world implementations. The framework has two layers (see illustration below). The framework was developed through iterative consultations with experts spread across technical and governance subject matter areas.

The first layer of the framework is inductive. It proposes a set of normative attributes, a set of common technological and governance qualities that describe how DPIs should be designed. The second layer is deductive. It is composed of a set of outcome indicators that describe how attributes can be realised in real-world deployments.

The framework identifies six attributes

| # | Attribute | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Interoperable and extensible | Interoperability refers to the ability of digital systems and components to communicate with each other, reflecting the ‘infrastructure’ nature of the technology. Extensibility refers to the ability of the technology to be foundational and bare-bones, such that it can be stretched to build its functionality as needed. It reflects the relevance of the technology to a diverse set of public and private actors using it as infrastructure to serve societal outcomes. DPI can also favour modularity, reflecting its composition of a set of building blocks that can be put together or broken apart as necessary. It can also be federated and decentralised, to allow an amalgamated set of services to serve one function. Technology with both open as well as closed (or proprietary) source code can be interoperable and extensible. However, the norm of interoperability favours open standards so as to facilitate higher adoption among more actors in a consensus-driven way |

| 2 | Transparency, accountability and oversight | Transparency reflects the quality of DPI being open and accessible regarding its processes and outputs throughout the design and adoption process. Accountability and oversight reflect the role of system operators and governors in ensuring that the digital technology, now essential to the functions of society, can be trusted by its users and by society at large. It implies accountable design through technology’s design features, as well as external accountability as ensured through oversight by legal actors in society. |

| 3 | Privacy, safety and security | Given the inherent access that DPI has to personal information and data, protecting this information against threats to privacy, safety and security of individuals is a necessary norm for DPI to be trusted by its users. |

| 4 | Non-discrimination and inclusion | DPI can exacerbate existing issues around individual access to basic services, curtailing human rights. For DPI to be inclusively designed, it needs to not only accommodate peripheral access, but keep inclusive design at the centre of its philosophy. |

| 5 | Capacity and coordination | Reflects the institutional arrangement within which the implementation of DPI is housed. For states, this refers to the novel and existing capacity that needs to be developed to respond to the DPI mandate. This capacity could house the DPI itself or be tasked with coordinating with non-state actors to implement the DPI. |

| 6 | Scale of adoption | The adoption of DPI by multiple agencies for public service delivery is an intrinsic DPI norm because it reflects the success of its ‘infrastructure’ potential. This attribute also hints at the interoperability, reflecting whether agencies (state or non-state) other than the one where the DPI is housed, can communicate with this piece of infrastructure. |

These attributes describe the qualities that define artefacts - like digital identity systems - as public (and not private) infrastructures. In addition to the four attributes, an essential condition to implementing DPI is the supportive ecosystem capacity and coordination capability. A final component for assessing DPI’s attributes is through the adoption of DPI, or the extent to which actors other than the DPI operator leverage the DPI.

These attributes should be read in framing DPI as the means to serve foundational societal functions in the digital age, namely digital authentication, digital transactions and the exchange of data.

To assess the attributes of real-world deployments, the DPI Mapping team had to determine: how do we know if DPI is interoperable? Do we look at its technical standards, or whether the architecture is made accessible through documentation? Or both?

The resulting set of outcome indicators sought to elaborate on the attributes by describing effective norms, rules, technologies and processes observed in real-world deployments and suggested by expert practitioners and area specialists (e.g. privacy and security experts).

Each foundational DPI (i.e. ID, payments, data exchange) has both unique and shared indicators. (38 for ID, 20 for payments, 20 for data exchange).

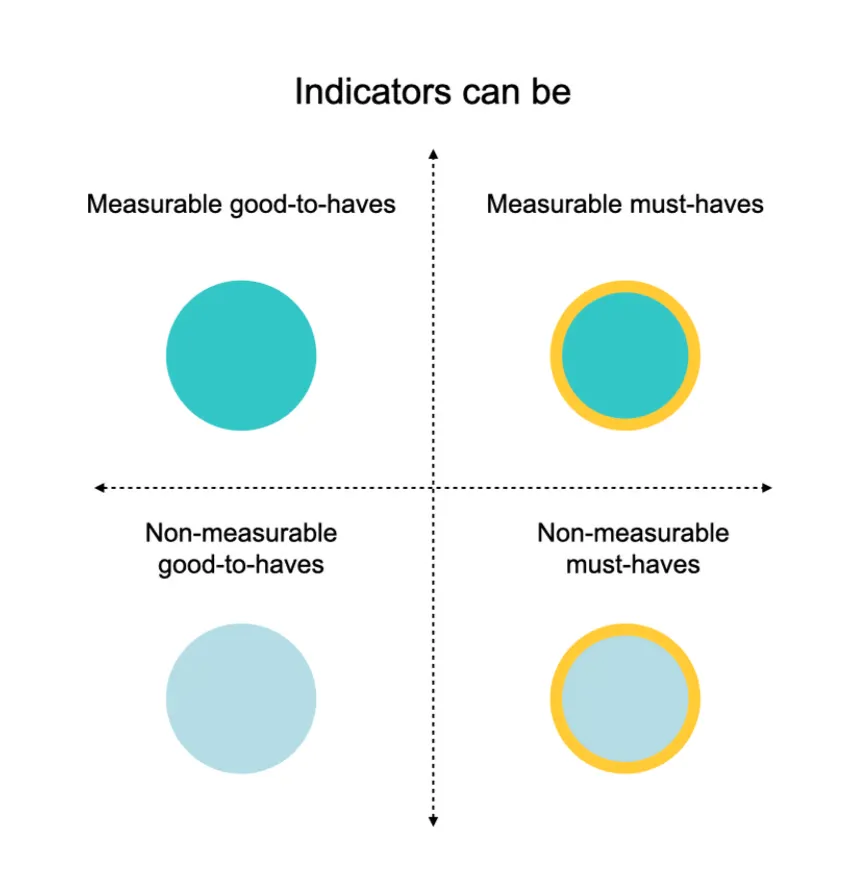

It’s worth mentioning that not all indicators are equal.

In version 1.0 of this framework, we present an exhaustive version of indicators for all attributes. These indicators however can be divided into subjective and objectively measurable (based on our data scoping methods, accessible here). We further divided indicators into two other categories: ‘must haves’ referred to indicators that more directly assessed the essence of an attribute, while ‘good to haves’ reflected those that did so more indirectly or partially. In an effort to both be more objective and make effective use of our limited resources, version 1.0 of our map collects data on only measurable must-have indicators.

We purposely share all the indicators we derived for several reasons. First, we hope users and contributors might suggest edits that would shift non-measurable indicators into being measurable. Second, that our list of indicators might inform others’ research. And third, just because an indicator is non-measurable does not mean it is not important. We hope that policymakers and DPI developers will find all our indicators useful when developing or deploying DPIs.

DPI Indicators for Digital Identity Systems

| # | Indicator |

|---|---|

| Interoperable and extensible | |

| 1.1 | Individuals can authenticate themselves or their documents digitally |

| 1.2 | Policy preference for a government-wide digital and interoperable ID system exists |

| 1.3 | Vision and strategy of the interoperability of the ID system as DPI conveyed transparently |

| 1.4 | Documentation for services to use ID system architecture is publicly disclosed |

| 1.5 | Procurement guidelines for technical vendors specify interoperability through data, standards, APIs |

| 1.6 | Technical standards and specifications of the ID system are compliant with international standards |

| Transparency, accountability and oversight | |

| 2.1 | ID system and its operations are under the purview of relevant Freedom of Information Laws, towards addressing corruption |

| 2.2 | Institutional governance structure and its accountability are established |

| 2.3 | ID authority is subject to general oversight of the courts |

| 2.4 | Accountability of the ID executors to the ID authority is established |

| 2.5 | Legally-binding redressal framework for ID-related malpractice is established |

| 2.6 | Procedural rules for collection, storage and sharing of personal data related to ID system are established |

| 2.7 | Government exceptions for using ID system and its data for national security, public order or other government interests are codified in law |

| 2.8 | Credentials issued by the DID are treated as legal proof of the elements recorded by the ID |

| 2.9 | Accountability of institutions recording personal data and their responsibility for digitalisation are established |

| 2.11 | ID system is informed by a multi-stakeholder group of representatives (especially from civil society, domain experts) |

| 2.12 | ID authority performance and ID system governance is regularly reviewed and reported |

| Privacy, safety and security | |

| 3.1 | Personal data linked to the ID is under the purview of the DPA and protected by law |

| 3.2 | Procedural rules for the ID (enrolment, data processing, issuing credentials, etc.) are established |

| 3.3 | There exists a process to notify individuals and general public about personal data related to ID system leaks or threats |

| 3.4 | ID-related personal data collection, processing and sharing is based on individual consent |

| 3.5 | Data protection authority regulates ID data collected and shared by the ID Authority and executors |

| 3.6 | Data and system security standards are publicly disclosed |

| 3.7 | ID system data and cyber resilience are regularly reviewed and strengthened |

| Non-discrimination and inclusion | |

| 4.1 | Processes to access, review, edit and delete one's ID data are transparent |

| 4.2 | Enrolment in DID is possible without discrimination |

| 4.3 | DID is not the only legal document to serve as a credential for accessing basic human rights |

| 4.4 | Cost of enrolling for the DID is affordable |

| 4.5 | DID is designed with inclusive access features |

| Capacity and coordination | |

| 5.1 | Processes to leverage the ID system across all levels of government are established |

| 5.2 | Budget for management of identification is dedicated, reliable and sufficient. |

| 5.3 | Strategy for skills training and retention is established |

| 5.4 | DID use across government is facilitated through a coordination body |

| Scale of adoption | |

| 6.1 | Public entities (that are not the same as the architect of the ID layer) use the ID infrastructure |

| 6.2 | ID infrastructure is used across more than 1 sector |

| 6.3 | Private entities use the ID infrastructure |

| 6.4 | Civil society actors use the ID infrastructure |

DPI Indicators for Digital Payment Systems

| # | Indicator |

|---|---|

| Interoperable and extensible | |

| 1.1 | Payment system policy prefers interoperability between PSPs |

| 1.2 | Payment system facilitates cross-domain and/or domain-specific interoperability |

| 1.3 | Payment system has the infrastructure to facilitate (near) real-time settlement of transactions between users |

| 1.4 | Documentation for PSPs to use RTPS architecture is publicly disclosed |

| 1.5 | Technical standards/ specifications are compliant with international standards/specifications |

| Transparency, accountability and oversight | |

| 2.1 | RTPS is governed by a central bank/ financial regulator |

| 2.2 | RTPS is transparent about the rules and conditions of participation |

| 2.3 | Non bank RTPS services are subject to payment system rules |

| 2.4 | Payment system operator performance is regularly reviewed and reported on |

| 2.5 | Payment system design is informed by a multi-stakeholder group of representatives |

| Privacy, safety and security | |

| 3.1 | Procedural rules for the RTPS's data handling are established |

| 3.2 | Fraudulent transactions on the RTPS are proactively prevented and managed |

| 3.3 | RTPS is subject to relevant security compliance and consumer protection laws |

| 3.4 | There exists a process to notify individuals and general public about personal data related to the RTPS data leaks or threats |

| 3.5 | Personal data linked to RTPS is protected by law |

| 3.6 | RTPS uses unique aliases to encrypt personal information |

| 3.7 | Merchants accepting retail payments are subject to security and fraud prevention compliance measures |

| 3.8 | There exist laws and institutions that individuals can seek protection under if their rights are infringed or they are discriminated against through the payment system |

| 3.9 | Data and system security standards are publicly disclosed |

| Non-discrimination and inclusion | |

| 4.1 | RTPS enables key transaction types for financial inclusion: P2P, G2P payments |

| 4.2 | Transactions are enabled through multiple access channels and non-digital means |

| 4.3 | Transaction fee for retail users is low/none |

| Capacity and coordination | |

| 5.1 | Budget for management of payment system is dedicated, reliable, sufficient |

| 5.2 | Strategy for skills training and retention (improving the interoperability and efficiency of the payment system) is established |

| Scale of adoption | |

| 6.1 | Public entities (that are not the same as the architect of the payment system) use the payment system for G2P/P2G transactions |

| 6.2 | Private entities use the payment infrastructure to accept retail payments (P2M) |

| 6.3 | Private entities use the payment infrastructure (B2B) |

DPI Indicators for Data Exchange Systems

| # | Indicator |

|---|---|

| Interoperable and extensible | |

| 1.1 | Semantic interoperability within the DES is facilitated through either policy or technical means |

| 1.2 | Data is shared in (near) real-time through the DES |

| 1.3 | Technology architecture of the DES is scalable |

| 1.4 | Data exchange has a federation capability |

| Transparency, accountability and oversight | |

| 2.1 | A public-interest entity governs the development and operations of the DES |

| 2.2 | Use of the DES is subject to transparent enrollment and participation conditions |

| 2.3 | Data exchange instances within the DES can be monitored in public-interest |

| 2.4 | Data exchange governance is regularly reviewed and reported on |

| 2.5 | Data exchange governance is informed by a multi-stakeholder group of representatives (especially from civil society, domain experts) |

| Privacy, safety and security | |

| 3.1 | Procedural rules for the DES (access restrictions, protections, etc.) are established |

| 3.2 | Personal data on the exchange is protected by law |

| 3.3 | Data and system security standards are publicly disclosed |

| 3.4 | Data exchange is regularly reviewed for data protection and cyber resilience |

| Non-discrimination and inclusion | |

| 4.1 | Data exchange across government is implemented by a coordination unit |

| 4.2 | Strategy for skills training and retention is established |

| 4.3 | Budget for management of the data exchange is dedicated, reliable, sufficient |

| Capacity and coordination | |

| 5.1 | Public entities (other than the operator of the DES) leverage the data exchange |

| 5.2 | Data exchange is cross-sectoral |

| 5.3 | Private entities leverage the data exchange |

| 5.4 | Civil society entities leverage the data exchange |

Using the framework

We hope that researchers, policymakers, technical advisors, and advocates will use this framework to advise and inform the measurement of DPI as a concept. A complete list of works consulted directly or indirectly in developing this framework will be accessible in our upcoming whitepaper. Feedback is welcome and will be integrated with subsequent versions.

Download the framework (Google Sheet) here.

Read the codebook to understand how the Map uses this framework.

Download the full PDF of the report here

Citation

Eaves, D. and Rao, K. (2025). Digital Public Infrastructure: a framework for conceptualisation and measurement. UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose, Working Paper Series (IIPP WP 2025-01).

Data collection methodology

The DPI Map puts the ‘Measuring DPI’ framework to the test, reporting a mix of data points from publicly accessible data sources. Typically, these sources include government-reported updates through their websites, press releases, as well as data from other third-party reporters (World Bank, UN, regional development banks, regional technical capacity-builders).

Since the release of the first version of our Map, we have also received data from country-level implementers and advisors, on the state of their country’s DPI. These have since been validated and included in the dataset as well.